Avoiding Small Mistakes (and big ones)

Applying lessons from real life to test prep, and vice versa

I’ve been writing a lot about mistakes in this Decision Hygiene series: Availability Bias, Loss Aversion, the Halo Effect, and many others. Today, I want to start writing about solutions.

One interesting thing about solutions – they work just as well in low stakes situations as they do in high stakes ones. A process that saves lives in a hospital can help you avoid mistakes on the SAT. And, more importantly, the habit or process you develop during test prep could help you avoid mistakes in a hospital, or a courtroom, or a cockpit, or any number of critical situations in life.

In 2001, Dr. Peter Pronovost discovered a staggering statistic at Johns Hopkins Hospital: 11% of patients with a central line were getting infected within a ten-day period. A central line provides a direct pathway to the bloodstream. It’s usually hooked up to a huge vein, like your jugular. Therefore, any infection of a central line will spread quickly throughout the body, leading to sepsis and, quite frequently, death.

Luckily, Dr. Pronovost was able to find a simple solution to this terrifying problem…a five-step checklist:

Wash hands with soap.

Clean the patient’s skin with antiseptic.

Put sterile drapes over the entire patient.

Wear a mask, hat, sterile gown, and gloves.

Put sterile dressing over the insertion site once the line is in.

The doctors and nurses at Johns Hopkins were already aware of these precautions. They believed they were important and knew how to implement them. Yet when everyone used the checklist, the ten-day infection rate dropped from 11% to zero.

This approach didn’t just work at his hospital. When Pronovost’s checklist was adopted by the Michigan Health and Hospital Association (the Keystone Initiative), they saved 1500 lives and $175m. A version of it has since been adopted by the World Health Organization.

Interestingly, doctors and nurses didn’t want to implement Pronovost’s checklist: “What appears to happen is oftentimes the staff do not see the benefit of the checklist and feel it is cumbersome to use, slowing them down with patient care. Therefore, they choose not to use it. On the other hand, when the staff was asked, ‘If they were having an operation would they want the checklist to be used?’ ...93% said yes.”1

I borrowed the phrase “decision hygiene” from Noise, which describes many of the same cognitive errors I’ve covered in this series of posts, and many effective remedies as well. I love the phrase, because it captures both the importance and irritation of healthy routines. When I was a little kid, I didn’t want to wash my hands before eating. Washing my hands seemed like this random thing I had to do that had a tiny chance of avoiding some probably-imaginary bad outcome and mostly served to block me from my goal of EATING RIGHT NOW. What disease was I preventing exactly?

And yet this generality is exactly what makes a good process good. Dr. Pronovost did not know what disease would be prevented by following his checklist; any number of bacteria could make their way into the hospital, and eventually, the hapless patient. He simply knew that the infections would not occur if the checklist was followed.

I hesitate to relate this to test prep, because the stakes are so much lower on the SAT and ACT. Nobody is in danger of losing a limb (or a life), as they might to sepsis. And yet, I do feel that the mistakes and solutions in test prep are very similar to others in the real world. The context is different, but the impulses are the same.

Reading is perhaps the most difficult score to improve in test prep. This is partly due to the overwhelming temptation to end the misery (which is what students really want). These passages bore most students. There are so many other things they would rather be doing. Picking a seemingly-good answer ends the pain… but often results in a bad score.

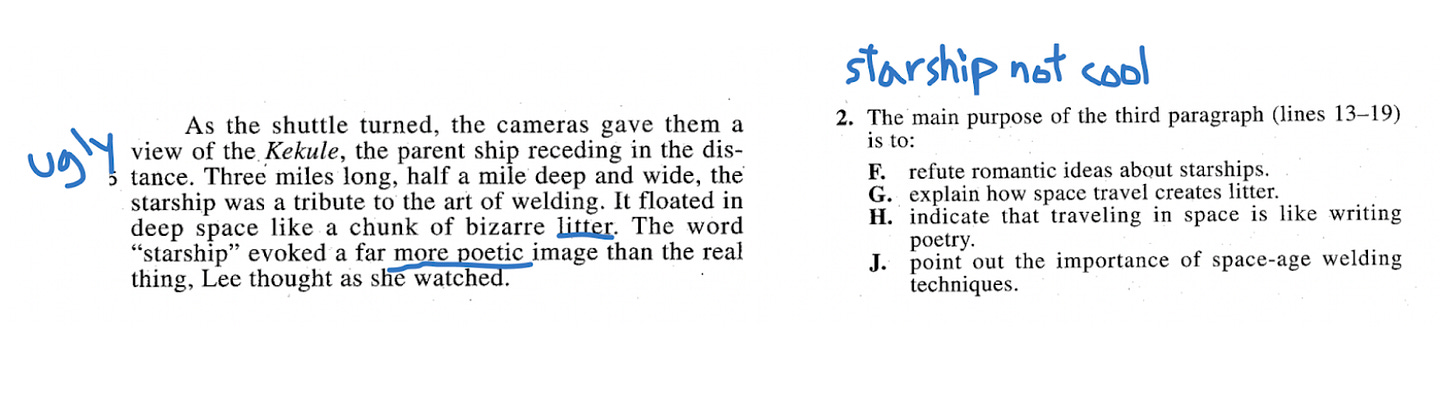

Students don’t process this paragraph very well:

They often don’t realize that the author is mocking the appearance of the starship (“a chunk of bizarre litter”). When they are asked for a summary, they will often glance back at the paragraph. There they notice words like ‘starship’, ‘litter’, ‘poetry’, and ‘welding’, but the paragraph still seems a bit weird. The first (and, as it turns out, correct) answer seems wrong because of the word ‘romantic’. But one of the other answers will usually grab them, because each contains a word that appeared in the paragraph. Seeing that word in the answer generates a warm feeling of familiarity.

A good process can protect them from these errors.

1. Take Notes - Make Sense of What You Read

The notes don’t have to be long or impressive – I just underlined a couple things and wrote ‘ugly’. Merely taking a few moments to actively make sense of the paragraph will usually help students retain what they’ve read.

2. Go Back To Find Information

Most passages are 80+ lines long. This would just be one of 10 questions. It’s very unlikely that a student would remember this paragraph without looking back. Taking 10 seconds to review the paragraph and their notes will put them in a much better position to answer the question.

3. Come Up With Your Own Answer

This is the one everybody hates. It is so tempting to go straight to the answers and see if anything ‘jumps out’. Instead, it’s best to come up with your own answer, even if it’s something simple (like “starship not cool”). If you have your own answer in mind, you’re much less likely to be fooled by a bad answer.

4. Find Something Wrong With Three Answers

Traps like ‘litter’ and ‘poetry’ are much less tempting now that you know what you’re looking for.

5. Star Hard Questions

If you’re still not sure, put a star by it and come back later. Following this process will give you the confidence to move on from hard questions, leaving valuable time at the end for you to take a second shot at them.

Of course, this process is also irritating. It requires several acts of willpower to resist the constant temptation to relax and pick an easy answer. And yet, this process helps students avoid all kinds of errors. Like Pronovost’s checklist, it is not designed to protect you from one particular malady. Different students are vulnerable to different cognitive biases. But I can tell you that when a student completes this checklist – understands the passage, goes back to find relevant info, comes up with their own answer, finds something wrong with three answers, and marks it if in doubt – they are very likely to get the question right.