Availability Bias

Why students hate redoing missed questions

In an experiment recounted in Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow, researchers asked spouses, “How large was your personal contribution to keeping the place tidy, in percentages?” If couples were perfectly accurate, the two responses would add up to 100%. If both spouses were modest, the sum would be under 100%. Sadly, the results added up to more than 100%: both spouses thought they were doing more than their share of the work.

This is an example of availability bias, a phenomenon that directly affects test prep and many aspects of daily life. I remember the annoying chores I did vividly. But I don’t recall all of the chores my wife has done. I may not even be aware of many of them, or know exactly what each task requires. So my own contributions seem to occupy a larger share of the work in my mind – not because I actually did more work, but because I’m not including a lot of my wife’s work in the denominator.

News coverage can have the same effect. I was a little surprised to discover that diabetes is a more common cause of death than the flu1. I seem to recall many stories about deadly flu strains, but stories about diabetes don’t come to mind.

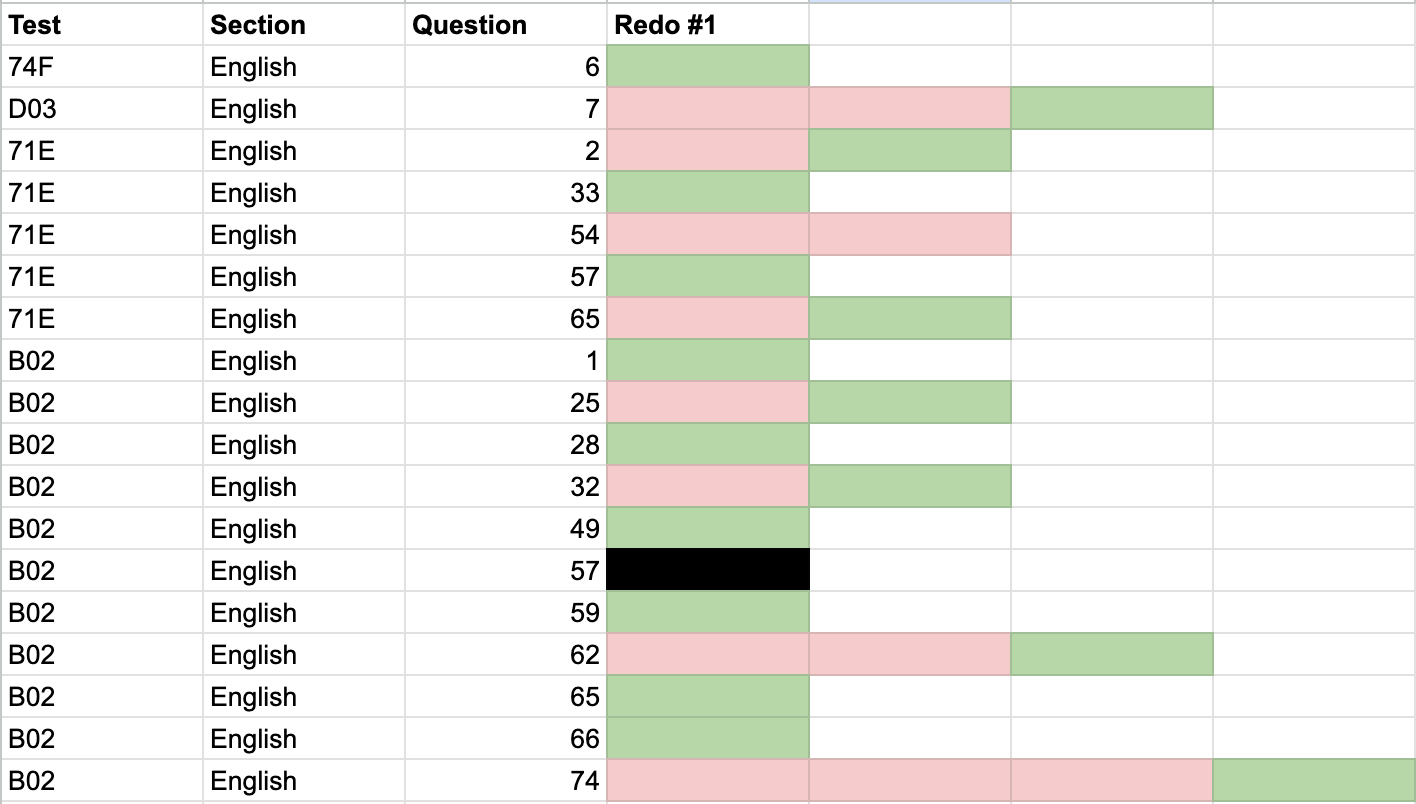

I notice availability bias in test prep when I try to get students to redo missed math and grammar questions from official practice tests. To me, the benefits2 of this task are obvious. The same question types show up over and over. If you understand every question from 10 official practice tests, nearly every question on your real test will seem like a thinly-disguised version of a question you know well from a previous test. At that point, all you have to do is recognize and execute.

Yet students absolutely despise redoing missed questions. And I can sort of see why. What do they get out of it? They can’t improve their scores on an old test. Best case, they get something right the second time around (which doesn’t feel like much of a victory). Worst case, they feel bad about getting it wrong again.

But I think part of the resistance is related to availability bias. Suppose I tell a student, “You missed some questions a while ago that are going to show up again on your test. Keep practicing them, or you’ll miss them again.” What comes to that student’s mind?

1. “Yes, I did miss those questions…but then you explained them, so we’re good.”

2. “Yes, I do still miss questions on tests, but those are different.”

Here’s what they don’t remember: redoing a missed question repeatedly, then seeing a similar version on a new test. To the student, every missed question is either a misunderstanding that has been cleared up or something completely new that still needs to be explained. He rarely has the experience of recognizing a question that he missed before and still doesn’t understand. Of course, it’s a catch-22: he won’t recognize old problems in new forms unless he practices them. And if he doesn’t recognize them, he won’t get them right. So he therefore does not recall any benefit to redoing missed questions!

The last time I ran the numbers, my students’ median English score was a 35. I attribute this mostly to the power of systematically redoing missed questions.

I love the idea of spaced repetitive review on missed questions! Do you have a system for getting your students to do this or is it just a simple spreadsheet like you show above?