How Mistakes Happen

Decision Hygiene #6: The "internal feeling of completion"

This is my 6th post on the topic of Decision Hygiene (see others here).

What do students want when they are answering test questions? They will say that they want to choose the right answer, but I don’t think that is quite accurate. I think most students actually want…

1) …to be done. There are generally other, more fun things they could be doing.

2) …to feel that the answer is right. If something ‘clicks’, or feels plausible in some way, they’ll have permission to be done and the satisfaction of feeling correct.

This brings us to an unpleasant truth: Feeling is an important part of any decision-making process. Even if you have a perfect process, you’ll still probably note how you feel about the result. You’ll want to feel good about your result before you move on. The authors of Noise refer to this positive sense of your answer as an internal feeling of completion. It’s a little reward we give ourselves when we get to the end of a decision-making process.

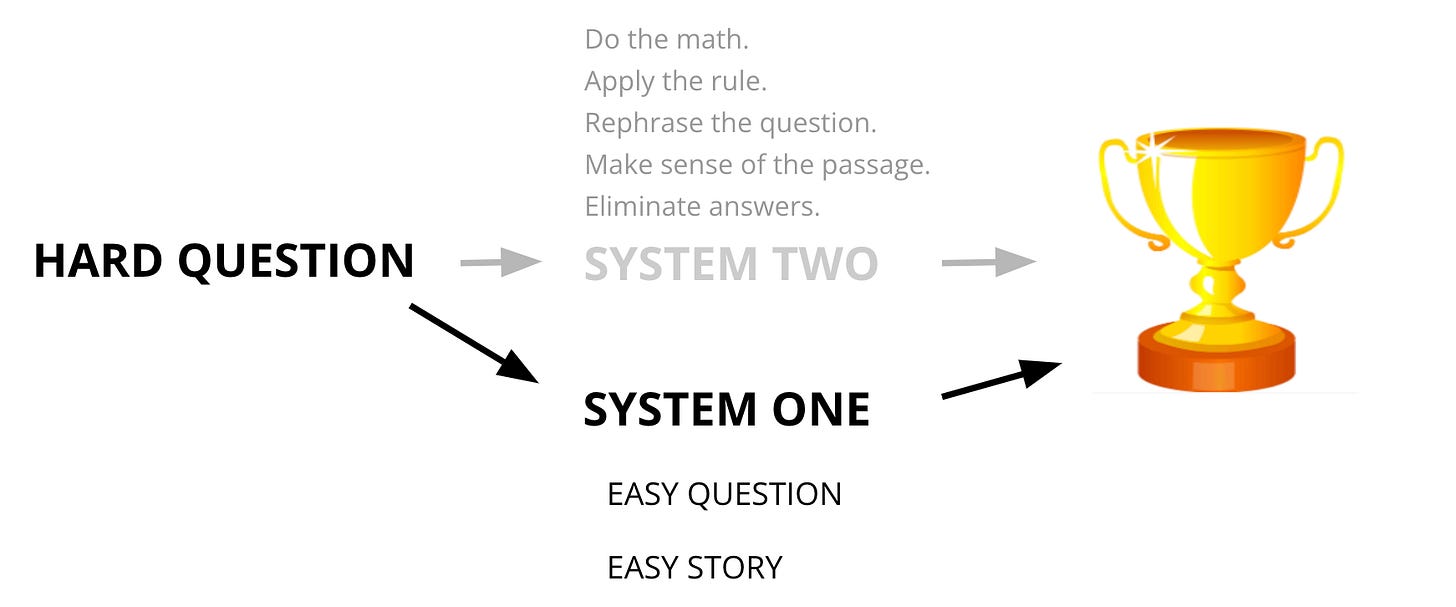

Sadly, you can sometimes you feel that you are right when you are actually wrong. But once you are holding that little trophy, you really don’t want to give it up. The Noise authors note that we value coherence over completeness. If you have a coherent story, you’d much rather keep that story (and the satisfaction of feeling correct that goes along with it) than go off looking for more details. That search for details will ultimately require a lot of cognitive effort (via System 2), and at the end of the search you may feel much less certain of your answer. So it’s more work and you have to give up the trophy! Net result: once you have that feeling of being correct, new information is unwelcome.

We see this unfold on standardized tests all the time. I always tell students to 1) go back to find information 2) think of your own answer first and 3) rule out wrong answers. But many of them prefer to jump straight to the answers and see if something “jumps out” at them….which leads them directly into a trap.

Students are often not sure of how to answer this question about Alhazen. There are lots of old, unfamiliar names throughout the rest of passage1, each paired with an old, slightly technical theory of how the eye works, and they don’t recall exactly who Alhazen was or what he thought. But a lot of them do vaguely recall something about a camera (as mentioned in choice B), and when they scan the paragraph about old Alhazen, they do see a camera! So now they have a coherent story: “The question is about Alhazen. I went to the paragraph about that dude. It said something about cameras. This answer says something about cameras….we’re done!”

Unfortunately, this is incorrect. He apparently thought it worked like a camera, but he did not actually make any plans to build a camera himself. (He did stress the importance of light later in the paragraph, though.)

Some variation of the flawed process shown above tempts us in all standardized tests: You’re faced with a tough question. You could work within a rigorous process that’s designed to gather relevant information and avoid errors…But that would require a lot of work. You might have to rephrase the question, or show your work, or go back to compare a couple graphs and charts. So instead, you substitute the hard question (“What was Alhazen’s contribution?”) with a much easier one (“Do I remember this from the passage?”), craft a plausible story (“it’s in the passage and it’s in the answer”), and grab your trophy.

I’m only showing one question, and the part of the passage that corresponds to it.