Students Learn More When They Choose

Another learning theory I like

Last month, I wrote about 10 learning theories that have been very useful for Mathchops and my own tutoring. Today, I want to write about a theory that is just as important to me…but for which I unfortunately have no evidence1.

I believe students learn more when they choose their work.

Now that doesn’t mean that they can choose whatever they want. They don’t analyze Taylor Swift’s lyrics for their ACT reading homework, or play Block Blast to work on SAT Geometry. They get to choose…but only from a limited set of options.

It’s like the options I give my kids at home: “Would you like to clean the kitchen, read a book, or go outside and play?” If my son is excited to go outside, great. If my daughter wants to read a book, terrific. I’m even open to negotiation – you’d like to play the piano instead? Go ahead!

Similarly, I try to give my students healthy options whenever I can. Would you rather work on our “top 100” math list or redo missed questions from Bluebook? This reading exercise or that science timing drill? If I want them to do a practice test or achieve certain Mathchops goals, they don’t have as much choice – they’ll have to complete those tasks at some point during the week – but they can still choose when and how they complete the tasks. Some choose to do a little every day, while others do it all the night before we meet.

Part of the theory is that there’s a point at which my preferences are not as important as a student’s enthusiasm. It’s better for them to lock in (as the kids say) on my third-favorite task than it is for them to slog their way through my favorite task. I don’t want the attention they bring to the 20 pages of history they have to skim by Friday. I want the attention they bring to a performance: sitting at the piano, with 100 people in the audience, hands just above the keys.

Mathchops makes a lot of the same sacrifices. In the early days, there was really only one game, and it fed students a stream of questions that were right at a student’s upper limit. These were the highest-value questions, the ones I most wanted a student to answer. Most students got 50% correct…and hated it. Getting so many questions wrong was too painful. I had to force them to use it every week, and some ultimately quit using the app.

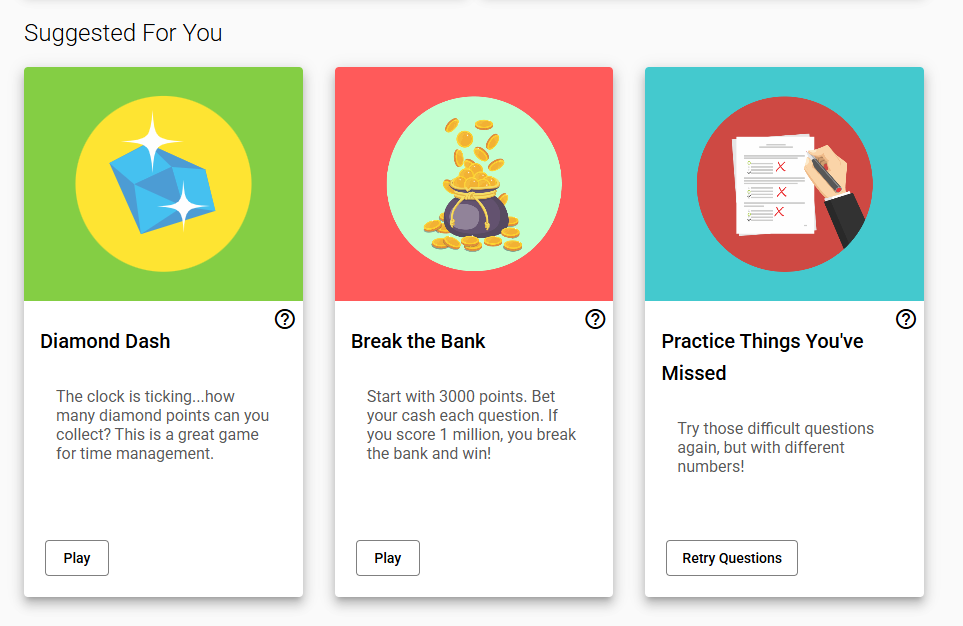

Now my students have more choices. If they want to increase their scores, they can play the Level Challenge. If that game is currently too hard, but they want to achieve that higher score some other way, they can earn it in a specific category (like Linear Equations or Geometry). And if they want to create their own quizzes, or play a game that’s a little more fun (like Break the Bank), they can do those things too.

Students get more questions right now (closer to 70%, on average). I think that’s partly because they aren’t seeing the hardest possible questions they can handle. But they are answering many more questions – at least twice as many. And that means they are actually answering more hard questions than they were before. They just have some easier ones mixed in (which is actually good for reinforcing old concepts anyway).

So, both in tutoring and in Mathchops, I’ve seen students answer more questions, take on harder challenges, and ultimately improve more as a result of getting to choose their work.

And I hope there is one more benefit. If my student is driving, but I’m telling him where to turn every time, does he really know how to get where he’s going? But if he makes every choice, even if from a limited set of options I provided, he’s not too far from doing everything on his own. The next step is to not give him options and only provide feedback as needed. And when the feedback isn’t needed…then I’ve really done my job.

It may exist, but I haven’t read much about it.