Good Tutors Love Wrong Answers

What is the optimal percent correct on a homework assignment?

Tutors and students want the same thing: higher scores. But they disagree about how to get there. Students want to get every question right. Tutors want information. And this usually means that we want students to get a lot of questions wrong.

As I mentioned in The Great Candy Hunt, we have a search problem. The student doesn’t know what’s on the test. The tutor doesn’t know what a student knows. So you have to work together to find high-value questions – the ones that show up a lot on real tests, that the student hasn’t mastered yet, but could learn fairly easily.

But how do you find these questions? Conversations can provide clues, but nothing is more informative than a wrong answer. When a student answers “8/5” to the question “What is the slope of a line perpendicular to 8x + 5y = 7?,” I know a lot more than I would if she told me she wasn’t comfortable with the concept of slope. Once I know she needs help with this specific variation, I can teach it very quickly, and it won’t take much work for her to maintain it. But I have to know she needs help with it.

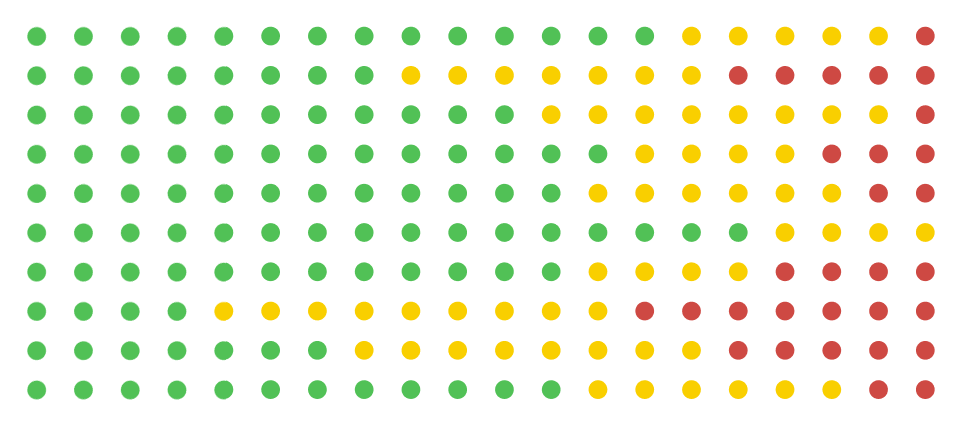

So we actually want students to miss a lot of questions. And this raises an interesting puzzle: if students didn’t mind getting questions wrong, what would be the optimal percent correct on a homework assignment? Not 100% – then they wouldn’t find many new ones. Not 0% either – that would mean they weren’t keeping the recently-learned questions fresh. Paradoxically, the more talented the student, the lower the optimal percentage, because they don’t need as many repetitions to reinforce previously learned material. Whatever number you think is best (most tutors fell between 50-70% when I ran a poll earlier this year), it’s certainly much lower than the percentage students are used to on tests in school, which is at least 85% in most classes.

In any case, my puzzle is irrelevant, because students hate getting questions wrong. They don’t like the feeling, first of all. But they find the rest of the process unpleasant too: dwelling on why the mistake happened, running through various ways to prevent it, then having to practice this same question type in various forms multiple times so that they don’t miss it again. A wrong answer basically equals ‘low score’ and ‘more work,’ both of which are unappealing.

And yet, wrong answers are the key to improvement! You can’t correct errors if you don’t know they exist. But if you do find them, then you can correct them. And there aren’t that many question types on these tests. The same skills show up over and over. In fact, they have to – otherwise, it wouldn’t be a standardized test. If you methodically seek out these errors, neutralizing them one by one, the testmakers will eventually run out of questions that surprise you.

Getting students to understand this, to be excited about this, is yet another strange but incredibly important aspect of tutoring. It’s not content. It’s not a test-taking strategy. It’s not a motivational speech. But the students who improve the most are the ones who learn to get excited by mistakes. They ask about questions they guessed on, even if they got them right. They star questions on Mathchops, so that they can come back to them. They read explanations on questions that took longer than usual, to see if there is a better solution. They want to practice with the hardest tests, and to redo the hardest questions from old tests.

How do you help students reach this state? I won’t pretend that all of my students get there, but here are some things that have helped:

Never get frustrated by wrong answers. In fact, you should be excited if you’re seeing a new mistake from the student.

Explain your assignments. Why should they do it? Share your vision frequently, so that students can see for themselves how they’ll reach their goals.

Make the homework as efficient as possible. Students hate busywork. Nothing kills motivation like irrelevant questions.

Celebrate small victories. For example, let’s say they missed a question a few times on Mathchops, then started getting right, and then a version of it showed up on their practice test and they got that one right too. That’s a win! Make sure they realize that their hard work paid off.

Don’t lecture just because they got something wrong. Small mistakes happen. If they understand it, move on. Nobody (especially a teenager) wants to hear you go on and on about a mistake they already fixed.

Please add your own in the comments below!

This is what I tell my students. I prep them with "I'm hoping to get some great wrong answer here" before getting into the challenging problems. Then I congratulate them on helping by getting some wrong allowing for a great teaching moment.